WHERE’S WALLACE

I sail with my heroes, both alive and dead. I bring the late ones closer by reading books. As a loose rule I don’t read guidebooks and I don’t buy souvenirs – I take only tales, and leave only footprints. I sink deep into a place by reading about people.

Absorbing the human stories means that when you arrive, the characters are there. Pre-reading makes places more porous. I go to feel the spirits and soak in antiquity. Books make the experience richer, the people more real, and the places come alive. We have travelled a long way to sit with Alfred Russell Wallace.

Wallace, a British Naturalist, conjured the concept of natural selection, in parallel with Darwin, while feverishly ill on the island of Ternate in 1858. He cooked up the idea independent and unaware of Darwin’s thinking. He scratched out the essay: "On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely from the Original Type", now dubbed the Ternate Papers. He sent this off to his old mate Charles, prompting Darwin to publish "On the Origin of Species" in 1859.

I write this on the eve of Ramadan, with surround-sound prayer from the 148 mosques of Ternate, (in the Molucca Islands, otherwise known as the Spice Islands). It is a time of fasting, prayer, reflection, and community and I am here to immerse myself after reading Radical By Nature: the Revolutionary Life of Alfred Russell Wallace.

Ternate rattles and hums. The town has a sophisticated edge, a slightly more cultured feel about it than other places we have visited. It is home to the 49th Sultan, universities, KFC and spoken English. Curiously, Ternate is oddly naive about its Wallace connection; the significance is only emerging. Wallace made the “earthquake-tortured island of Ternate” home base for three years as he explored the Malay Archipelago in the mid 1800s. Present-day officials can’t quite agree on the actual site of the house he rented and this obliviousness only adds to the charm. Wallace notes:

“I found it very convenient to have a place to return to after my voyages to the various islands of the Moluccas and New Guinea, where I could pack my collections, recruit my health, and make preparations for future journeys.”

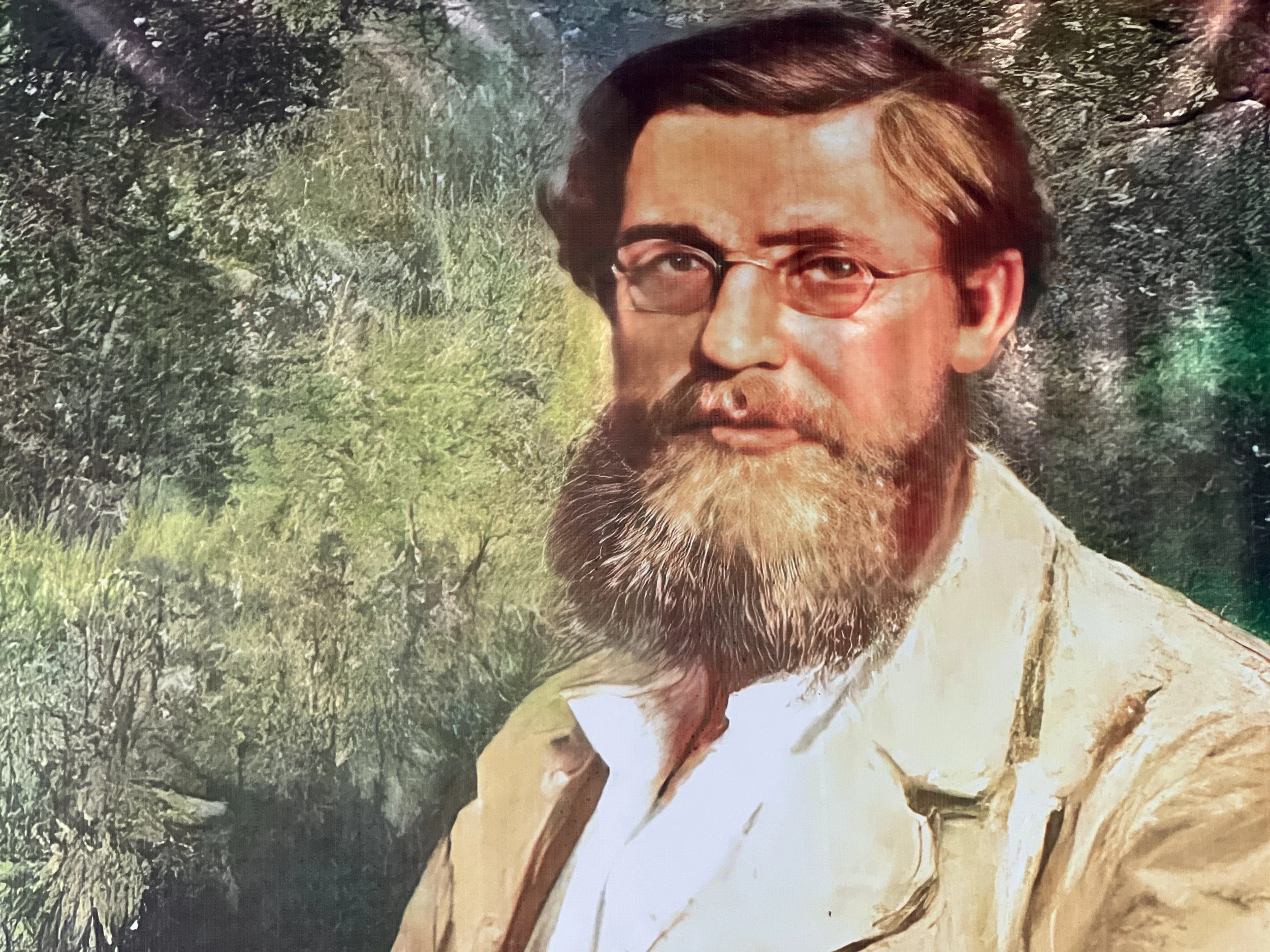

Through a process of elimination, puzzling, and various missteps, historians and local researchers have marked a spot. It’s as good as any, I guess. We visited the fairly non-descript humble abode. No museum, no stories, no fuss. Enthusiastic Javanese caretakers opened the locked door to show us a few pictures depicting Wallace at work, remnants of a well (described in Wallace’s diary), and we were the first to sign a Visitors Book as they peddled ‘Wallace Kopi’ (coffee).

They took photos of us, and we took photos of Wallace murals. Despite the lack of fanfare and information we sat and invited in the life force. Awash with anecdotes, the stories we had read swirled. Because of the book, we felt Wallace in this place.

Although Wallace’s impact is a shadow of Darwin’s, his legacy is marked by a line: The Wallace Line. The Wallace Line is a biogeographical boundary that separates the distinct wildlife of Asia and Australia, marking a division where Asian species such as tigers and elephants exist to the west, while marsupials, such as kangaroos, dominate to the east. The Wallace Line is the result of millions of years of geological separation, deep-sea barriers, and evolutionary processes. It is one of the strongest natural divisions of species on Earth, demonstrating how geography shapes the development of life.

The line is invisible, covert, like his legacy. Wallace was a humble character: his strength was crystallising his complex ideas in writing. Apparently he was a less impressive orator. He let others have the glory (Darwin), had an insatiable curiosity, was unapologetic in his obscure fascinations (seances, the afterlife, hypnotism), possessed intrinsic morality (abhorred slavery and championed woman’s suffrage), suffered heartbreak (romantic), heartache (death of a child) and heart issues (health); yet he lived a full 91 years.

Books summon souls. Because of books, I walked the cliffs on Auckland Island with Mrs Jewel, sailed on Steinlager 2 with Sir Peter Blake, enjoyed Fitzroy and Darwin’s friendship and chased traces of Shackleton, Robert Falcon Scott and Amundsen in the Ross Sea.

I have had the privilege of going to sea with many living legends too: Jo Ivory, Nic Charrington, Steve Bull, Wayne Karauria, Magnus O’Grady, Terry Dunn, Russell Harris, Ben Willoughby and Rodney Russ, to name a few. These sailors are avid readers, and some are writers. Readers know that books add depth to life and that adventures beget adventures.

I read about people, and I write about people, alive or dead, it doesn’t really matter.

“Reading is like breathing in and writing is like breathing out, and storytelling is what links both: it is the soul of literacy.” Pam Allyn

Book recommendations:

Radical by Nature: The Revolutionary Life of Alfred Russel Wallace, by James Costa

Mrs Jewel and the Wreck of the General Grant, by Cristina Sanders

This Thing of Darkness, by Harry Thompson

Peter Blake, by Marco Livingstone